|

WHY BRAZIL? The Belgian mobilization against repression in Brazil and its

significance for Third World solidarity activism in the 1970s

and beyond Overgenomen van Belgian Journal of History, Why Brasil?, 2013, 4 Kim Christiaens is a postdoctoral fellow of the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO), working in the research group of Modernity and Society 1800-2000 (MoSa) atKU Leuven. In 2013, he completed a PhD in History with the dissertation 'Orchestrating Solidarity. Third World Agency, Transnational Networks and the Belgian Mobilization for Vietnam & Latin America, 1960s-1980s'. He is currently working on a postdoctoral project on Southern European dictatorships and the emergence of human rights networks in Western Europe in the period between 1950 and 1975. More broadly, he conducts research on social movements, globalization and transnational networks during the Cold War, public diplomacy, East-West and North-South connections, Europeanization, and international human rights history. He is also a member of the Leuven Centre for Global Governance Studies. He has recently published articles in Vingtième Siècle, Dzieje Najnowsze and BTFG/RBPH, and has been a co-editor of the volumes The Transnationality of Social Movements, 1970-2010 and European Solidarity with Chile, 1970s-1980s (Peter Lang, 2014). He teaches the graduate course "Cold War history" at KU Leuven. Forseveral years, an inerdisciplinary range of scholars has begun to revisit the history of the European socicial movements that engaged in solidarity campaigns for distant Third World countries in the wake of postwar decolonization. This article aims to contribute to a new and more complex understanding of these and repression in Brazil in the early 1970s. Why did the plight of Brazil provoke such a groundswell of gone unnoticed in previous years and was quickly superseded by other international causes after 1973? By drawing attention to hitherto neglected transnational dimensions and networks, this article develops new perspectives to re-think the roots, development and shifting affinities typical of solidarity campaigns for Third World countries and human activism. In international historical research, there is nowadays a growing interest in the variety of European social movements that were, most notably since the 1960s, mobilized by issues in far-flung countries of what was then called the 'Third World' and is today mostly referred to as the Global South(1). Indeed, a plethora of groups started, in the wake of postwar decolonization, to claim solidarity with revolutionary political movements in the Third World, and turned distant crises in exotic countries into mobilizing campaigns within their Western European societies. Driven by a growing scholarly fascination with the roots and genealogies of human rights, transnational activism and globalization, an interdisciplinary array of scholars has in recent years started to revisit the history of these solidarity movements. What renders these movements so relevant to many historians is that they broaden the scope and show that globalization of social movements did not start in the 1990s, but was a historical process well under way before the end of the Cold War, in a period that lacked today's opportunities for travel and communication(2). This interest in analyzing the ways in which European activists broadened their scope beyond their own societies ties in with a broader 'transnational turn' in historiography since the 1990s(3). Rooted in critiques of the myopia and dominance of national frameworks of analysis in traditional historical research, transnational history focuses on connections and identities that linked societies across the mental and physical borders between nation states and regions(4). Recent generations of historians taking this transnational turn have then analyzed in great detail how a number of international crises and issues across the world moved over borders and regions to provoke a groundswell of activism in post-war Europe, as exemplified by the massive protests against the Vietnam War in the 1960s or the widespread criticism provoked by Pinochet's coup in Chile in 1973(5). In the 1960s and notably in the early 1970s, Belgium also became the setting for a plethora of social movements identifying with foreign political crises and movements in various countries of the Third World. Well-known examples are the solidarity movements that developed in support of the Chilean resistance against Pinochet and the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, or the growing protest against apartheid in South Africa(6). One of the less well-known but nevertheless most important examples of an international cause that provided a focus for domestic mobilization was that of Brazil(7). Since the overthrow of democracy in a coup in 1964, a wave of violence and political repression had swept the Latin American nation, ruled by a military regime that resorted to torture, murder and mass arrests in an attempt to suppress domestic protest against social injustice and state violence(8). Whereas the plight of Brazil had been ignored for several years, various sectors in Belgian society seemed in the early 1970s to be strikingly moved by the human rights violations, turmoil and injustice in the country. From 1970, a host of local initiatives sprung up to raise public awareness of the situation in Brazil, which as a result received attention from a broad variety of groups, ranging from Catholic and Communist organizations to human rights NGOs and the student movement. The mobilization reached its zenith in the autumn of 1973 when several thousand Belgian citizens took to the streets in massive protests against the international trade fair Brasil Export 73, which had been organized by the Brazilian government in Brussels. In addition, Belgium became the center of a global campaign developed by the Second Russell Tribunal, an international tribunal formed by a group of well-known intellectuals, which aimed to condemn human rights violations in Brazil before the world(9). This tribunal was officially constituted in Brussels in November 1973(10). This article aims to probe the reasons why the campaigns on Brazil resonated in Belgian society and to assess their broader relevance to the study of the broader history of Third World activism in the 1970s and beyond. Indeed, an analysis of these Belgian campaigns against the repression in Brazil is relevant for several reasons. In public memory and historiography, this groundswell of activism has until now remained an unjustly neglected topic, overshadowed by the more iconic protests against the Vietnam War in the late 1960s and against the coup by General Pinochet in Chile in the autumn of 1973(11). Nevertheless, the campaigns for Brazil were the first large-scale action against a Latin American dictatorship, preceding and influencing later campaigns for countries like Chile, Argentina and Nicaragua(12). As this article will argue, they provided, both organizationally and ideologically, the foundations of a locally embedded network of activists interested in Latin America throughout the 1970s and early 1980s. Beyond addressing a largely unknown topic, this article argues that the mobilization for Brazil offers an interesting case study to address a major gap in traditional research on Third World solidarity movements in Western Europe. Indeed, most historiography to date has explained the emergence of activism on behalf of distant countries like Brazil or Chile simply by looking at the motives and actions of locally organized Western activists, whilst ignoring the involvement of political movements in the Third World with whom the activists identified. There has been a powerful narrative that places the roots of campaigns for foreign countries with the growing numbers of Western activists for whom, since the 1960s, the drama and revolutions of the Third World offered a 'projection screen' for their own ideals and domestic struggles(13). Accordingly, European solidarity movements and their conceptions of the Third World have been presented mainly as issues of human rights concerns, moral indignation, imagination or the political agendas of Western activists(14). This interpretation has resulted in a focus on the ways in which activists 'domesticated' foreign issues and how their choice to align with the fate of the Third World was shaped by factors such as domestic ideology, instrumentality and political struggles at home(15). Yet, this narrative has also meant that to date little critical attention has been paid to the role of material connections between Western European activists and the Third World countries they campaigned for, and to the question of how political movements from the Third World were involved in the overseas mobilization on behalf of their causes both at the local and national level.

The catholic missionary Jan Talpe. Photo published with an interview about the torture of opponents by the Brazilian regime upon his return from the Brazilian jails, Der Spiegel, 15 December 1969, p. 98. On the face of it, there may indeed seem to be few indications of such connections in the campaigns for Brazil in Belgium, which hosted only a limited number of Brazilian exiles in the 1970s and had no important links with the Latin American nation. Whereas more than a thousand Chileans fleeing repression in their home country lived in Belgium after Pinochet's 1973 coup, the number of political exiles among the approximately four hundred Brazilians living in Belgium in 1970 appeared to be very limited(16). When leading Belgian activists spoke in the contemporary press about their engagement with Brazil, they sometimes, however, explicitly referred to their Brazilian inspiration. Asked by a critical journalist why Brazil had provoked so much campaigning whereas many other international issues went unheeded, the Belgian law professor and vice-president of the Russell Tribunal on Brazil François Rigaux answered : "Because these Latin American people not only asked us to do this, but they also gave us the opportunities to carry out our actions"(17). Similarly, recent studies on Brazilian exile have pointed to the ways in which these groups tried to reach foreign audiences, although we know little about their eventual impact in countries beyond France, which was one of the most important exile destinations, and the United States(18). More broadly, some innovative studies have recently hinted at the pivotal role of diplomats, exiles and foreign students in fueling the rise of Third World solidarity movements in Western Europe, trying to upset narratives which have portrayed the former as rather passive or imagined objects of Western activists' support(19). The most powerful and theoretically informed critiques of Eurocentric conceptualizations of activism and the limited attention given to the agency of Third World actors do not, however, come from historians, but from the impressive body of literature on transnational activism written by political and social scientists. Since the 1 990s, theories developed by authors like Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink have drawn attention to the role of Third World actors in the emergence of transnational networks and campaigns for their causes among overseas audiences(20). Traditional historians of the European solidarity movements of the 1960s and 1970s have, however, been slow to plumb these theories, which have been primarily based on empirical studies of more professionalized justice and peace NGOs(21). The role of transnational networks in the more politically oriented grassroots solidarity movements of the (New) Left as well as the agency of explicitly political Third World actors such as exiles and political parties have consequently received far less attention. This article aims to fill this gap and to contribute to a transnational revision of the Third World solidarity movements of the 1970s by asking specifically about the role of Brazilian connections in the development of local solidarity campaigns in Belgium. It raises the question of how activism in Belgian society was embedded in transnational networks which interlinked activists across state borders. Was the focus on Brazil simply a matter of domestic political conflicts and inspiration by Belgian activists, as asserted by the historiographers of 1 968 and student movements, or was it also rooted in connections with Brazil(22)? And, if the latter is true, how should we think about these networks' nature and function, and their concrete impact on local activism, both at the organizational and ideological level? Did the campaigns for Brazil suggest a Europeanization and globalization of local activism, or did the cross-border connections at work in the mobilization develop bilaterally between Belgium and Brazil? To answer these questions, this article draws on extensive research carried out in several archives in Belgium and abroad, as well as in various private archives held by former activists or organizations such as Oxfam-Belgium and the Fondazione Lelio Basso in Rome. It will gauge the importance of the mobilization for Brazil by comparing it with contemporary actions in other countries and for other international causes. First, this article analyzes how a transnational network set up by Brazilian exiles created spin-offs in Belgium, and how it fueled the emergence of the earliest activism and the foundation of the Second Russell Tribunal. It then turns to the central role which Belgian activists began to play in international campaigns against the Brazilian dictatorship as a result of the organization of the Brasil Export trade fair in Brussels in November 1973. After analyzing the shift of activists towards other Third World countries and issues, this study evaluates the impact that the mobilization for Brazil had on later campaigns for Latin America in Belgian society.

I. A transnational Brazilian exile network and the difficult quest for action in Belgium (1970-1972) In August 1969, the Catholic missionary Jan Talpe (°1933) arrived home in Belgium on a plane from Brazil. Talpe had been sent by the bishop of Bruges to Brazil in 1965 to work as a professor in physics and student chaplain at São Paulo State University(23). Inspired by liberation theology, social injustice and the growing repression of protests by the authorities, he had become active as a worker priest in the municipality of Osasco in the Greater São Paulo area, where he started to live with his fellow worker priest, Father Antonio Alberto Soligo, amongst metalworkers in the favelas. There they worked against a backdrop of growing turbulence, as protest against the dictatorship which had ruled the country since the 1964 coup started to spill over to various sectors of society (including students, trade unions and the Catholic church), culminating in massive demonstrations in 1968(24). In an attempt to squash this opposition and the resistance by radical armed groups, the Brazilian military government responded by extending repression(25). It promulgated Institutional Act No. 5 in December 1968, ushering in a wave of state terror and repression. As a result of this, the work of the two priests, Talpe and Soligo, came to an abrupt halt in February 1969: involved in political opposition, both clerics were jailed by the police and accused of subversive activities. Both priests were questioned and brutally tortured, like many hundreds of other dissidents(26). Only after several months of imprisonment and through the mediation of Belgian diplomats, was Talpe released, expelled, and put on a plane to Belgium, where he arrived full of dramatic stories, which he communicated in media interviews soon after his arrival(27). Whilst the situation in Brazil since the coup of 1964 had gone largely unnoticed in Belgium, Talpe's compelling story gained the interest of a variety of journals in Belgium and abroad(28). Talpe was not the only Belgian forced to leave Brazil : Conrad Detrez (1937-1985), a former seminarian who had left Belgium for Brazil in 1962 and who had become active in the radical armed resistance around the revolutionary guerrilla leader Carlos Marighella, had also returned to Western Europe. In Paris, Detrez worked, together with Marighella, on the book Pour la libération du Brésil, made translations of Brazilian literature and the works of the bishop of Recife Hélder Pessoa Câmara, before becoming a renowned novelist and literary icon of homosexuality(29). Some months after his forced return to Belgium, Talpe travelled to Paris to attend an international meeting organized on 15 January 1970 in the Mutualité, the famous meeting centre of the French Left. There, under the chairmanship of the Protestant Professor of Theology, Georges Casalis, the Belgian missionary took the floor together with some representative French intellectuals, including Jean-Paul Sartre and Father Michel de Certeau SJ, to discuss possible action against the repression by the Brazilian government of its domestic opposition(30). Around a hundred participants drawn from various French organizations as well as a host of visitors from other Western European countries, worked to form a network to make the repression in Brazil, and most notably the torture used by the military regime, an issue in Western Europe. The driving force behind this initiative, however, was not the prominent French intellectuals who lent style to this gathering, but the Brazilian exiles who had organized themselves as the Frente Brasileira de Informações (the Brazilian Information Front, with the rather ironic abbreviation, FBI). This organization had been established some two months earlier under the leadership of Miguel Arraes (1916-2005), the deposed Socialist governor of the North Eastern state of Pernambuco(31). Arraes was one of the hundreds of former left-wing holders of power who went into exile during the repression after the 1964 coup which overthrew the leftist president João Goulartand installed a military regime under Marshall Castelo Branco(32). Living in Algeria since 1965 and travelling across the globe under the protection of the government of Boumedienne, Arraes had, together with a number of like-minded exiles, founded this organization in Paris in late 1969 as the organizational heart of a network which developed branches in Latin America, Western Europe and the US and which aimed to mobilize overseas public opinion against the growing tide of repression in Brazil(33). In order to span the different ideological and political camps within the Brazilian opposition and exiles, the Frente set out to publicize information collected 'from all revolutionary organizations in Brazil' abroad, with the term 'revolutionary' covering a range from armed guerilla groups to Catholic groups

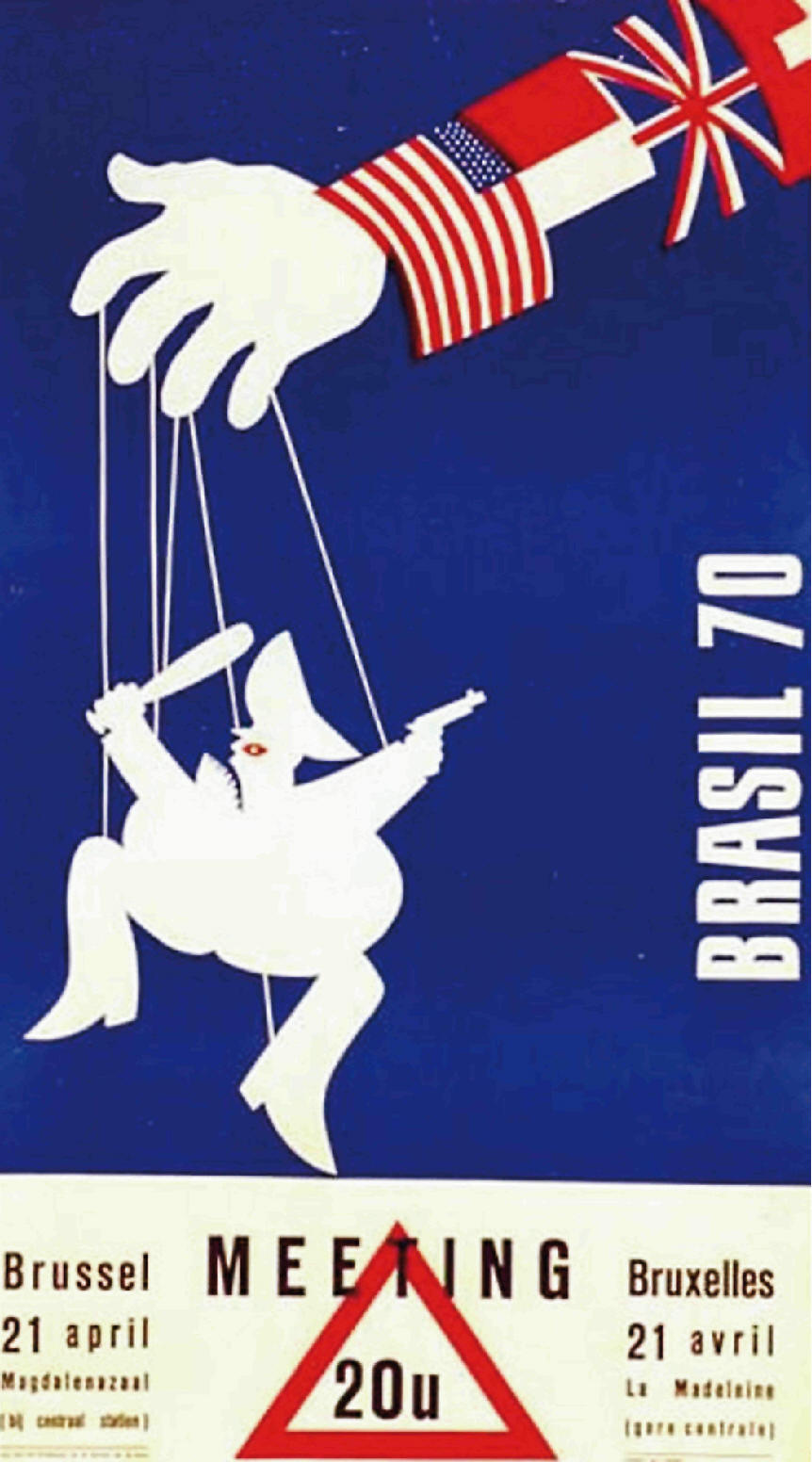

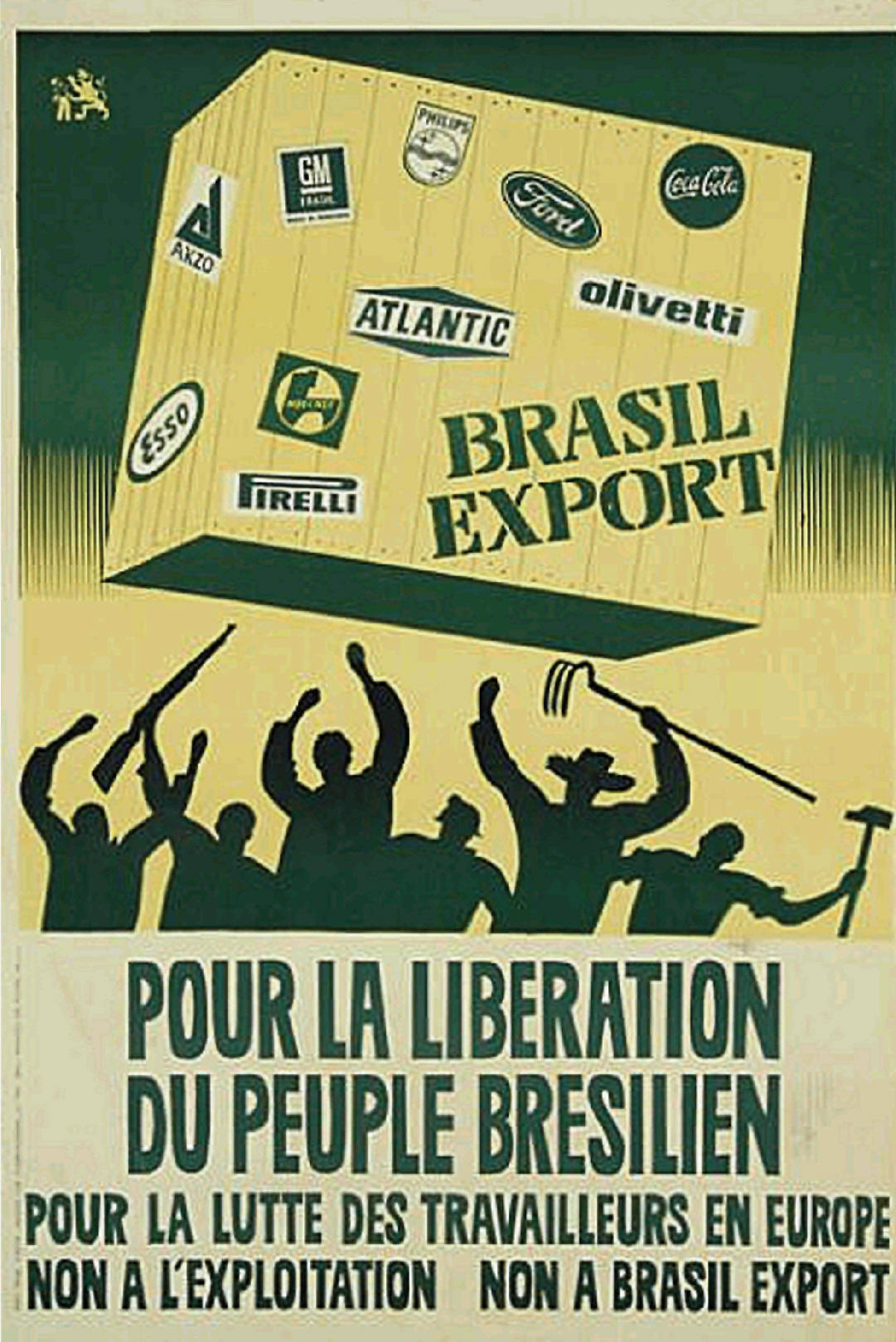

The Brazil national football team (Seleção Brasileira) led by the legendary Pelé won its third World Cup in Mexico in 1970. In the very same year, the FBI started to draw international attention to human rights violations in the "other" Brazil. The FBI and its Belgian branch cooperated with human rights NGOs like Amnesty International and the Belgian League for the Defence of Human Rights, which staged meetings to publicize testimonies on torture and repression by the military regime. This poster portrays the Brazilian government as a violent puppet in the hands of the US and Western Europe. (Archives AMSAB-ISG) After the coup of 1964 Brazilian political exiles were not a large group and were, before 1973, mostly based in Chile. In Western Europe there was a rather limited number of exile communities, most notably in Paris(35). The FBI itself had been founded by a few dozen key exiles, scattered across various countries and coordinated by Arraes in Algiers, which had developed into the capital of the non-alignment movement and which was a meeting center for a variety of liberation movements from Africa and other parts of the Third World(36). The network which formed around the FBI in the following months included both members of radical groups, some of whom had been released by the Brazilian government after high-profile kidnappings of diplomats, radical priests in exile, and more moderate figures like the journalist and congressman Márcio Moreira Alves, who had escaped to Chile(37). Given its limited organizational capacity, the FBI placed much emphasis on reaching out to audiences in Western Europe to draw attention to its cause. It was with this aim that Miguel Arraes organized the international conference in Paris in January 1970 where, beneath a huge portrait of the then recently murdered urban guerrilla leader Carlos Mari-ghella, he presented the newly founded exile organization and discussed what action could be taken to draw greater attention to the repression in Brazil(38). To break the silence in Western Europe about the repression in Brazil which had been growing since the inauguration of the second military president Artur da Costa e Silva in 1967, the FBI focused on denouncing the Brazilian authorities' use of torture, a subject which the Brazilian media did not discuss. This focus was prompted by the fate of hundreds of dissidents who disappeared or died at the hands of the Brazilian repression apparatus, or were jailed and tortured in increasing numbers under the reign of Emílio Garrastazu Médici. Médici assumed the presidential sash in 1969 and brought the persecution of armed resistance groups and opposition to its zenith(39). To pursue its campaign and document accusations against the Brazilian government, the FBI relied on accounts of former political prisoners who had escaped the country and joined the FBI network(40). Algerian examples also inspired the plans of the FBI, since this campaign paralleled earlier campaigns by the Algerian National Liberation Front to denounce torture by the French colonizers during the independence struggle(41).

As part of its campaign to publicize the use of torture in Brazil, the FBI encouraged the attendees to establish a European-wide net-work of so-called 'Europe Latin America Committees' with national branches in their respective countries. Operating in close cooperation with FBI sections in Western Europe, these committees were meant to engage in public campaigns about the repression in Brazil and about current developments in Latin America. Focusing on what was considered to be a 'human rights' issue rather than a merely political one, the committees were designed to appeal to audiences which had not previously been targeted by the Brazilian exiles, and to spread information as widely as possible. The shift of the FBI's focus towards human rights issues, also evident in its swift cooperation with NGOs such as Amnesty International and the International Association of Democratic Lawyers, makes a case for questioning claims by recent studies which have stressed the gap between Third World political movements and solidarity on the one hand, and Western discourses about human rights on the other(42). The example of the FBI shows not only how radical political groups amalgamated their cause with human rights discourses, but also how they shaped human rights activism and put the cause on the agenda of Western European groups. French participants built on the momentum generated by the meeting by creating a French section of the Europe Latin America Committee(43). Through other participants at the meeting the FBI's plans also found their way to other countries. Just as with the formation of the French and Italian committees, so-called 'Europe Latin America committees' were founded more or less simultaneously in several Western European countries, including in the UK, West Germany, Switzerland, and Belgium(44). In the UK, Brian Darling, professor at the university of Surrey and member of the editorial board of the French journal Esprit was the central figure(45). For Belgium, the missionary Talpe was the main connection in launching this initiative outside France. Indeed, after some weeks of press interviews and speaking tours, Talpe gathered together more than thirty interested people to form the Belgian Europe Latin America Committee (CEAL, Comité [belge] Europe Amérique Latine) in late February 1970, with the headquarters of Oxfam-Belgium in Brussels as the main center(46). The latter organization, founded in 1964 by a group of aged aristocratic philanthropists in the circle of Victor de Robiano (1907-87) and Antoine Allard (1907-81), became the financial and organizational backbone of the new committee(47). Under the leadership of the young activist Pierre Galand (°1940) and endowed with considerable resources, Oxfam had in the late 1960s become the central plank in a network which created important connections between organizations and people from different ideological backgrounds around common issues like peace and the Third World(48). Just as with the peace and disarmament issue and the protests against the Vietnam War, the situation in Brazil was used as a common cause to unite people and organizations beyond ideological divisions. Among the constituents of CEAL were not only a number of key figures of the campaigns against the Vietnam War including the leading peace activist Isabelle Blume and Louvain-la-Neuve professor of sociology and theology Canon François Houtart together with other activists close to the Belgian Communist party, but also representatives of Christian organizations which seemed receptive to campaigns on the situation in Brazil and Latin America. These included not only youth groups such as the Catholic Workers' Youth (KAJ), but above all some well-known respectable figures of the Christian trade union movement from the older generation, such as the peace activist and Pax Christi member Robert De Gendt (1920-2004) and August Cool (1903-1983), former president of the Christian trade union ACV/CSC(49). The doors of Catholic organizations opened relatively easily for the former missionary Talpe due to the concern in some Catholic quarters, notably within the Catholic Workers' Youth (KAJ) and sections in the Christian worker's movement, with what was happening in Brazil. Indeed at the same time that CEAL was being launched, Catholic groups in Belgium were paying increased attention to the situation in Brazil after assaults by the Brazilian military police on the Catholic Workers' Youth from 1969 onwards. The situation worsened further in the course of 1970(50). In response to the active role of the Brazilian Catholic Workers' Youth in staging protests against the regime, the military police invaded its headquarters in São Paulo and imprisoned various chaplains and leaders, charging them with "anti-state subversive activities"(51). When news of this reached the International Catholic Workers' Youth office in Brussels in September 1970, the group told its chapters to organize demonstrations of solidarity for the release of their imprisoned members(52). Like its counterparts in nearby France, West Germany, the Netherlands and in the United Kingdom, the Belgian Catholic Workers'Youth - in cooperation with allied organizations -sprang into action(53). Besides letter and telephone campaigns to the Brazilian embassy in Belgium and the Brazilian and Belgian Catholic hierarchy and government, a demonstration was organized on 17 October 1970 in Brussels, gathering between four and five thousand participants. There were also simultaneous demonstrations in other countries, such as in the Netherlands and West Germany(54). Undoubtedly, the Belgian Catholic Workers' Youth and the related organizations of the Catholic Workers' Movement were the driving force behind this protest. Yet, the newly founded CEAL played a constructive role in this campaign, helping the Catholic organizers to reach out beyond the borders of their own constituency to Communist groups, such as the Belgian Union for the Defence of Peace (BUVV), the peace organization of the Belgian Communist party. It was thanks to people like Talpe and other CEAL members that the demonstration of 17 October 1970 was an eclectic combination of Catholic nuns and priests, students from Catholic as well as Communist and other radical leftist organizations, and individuals active in Third World and peace groups. They marched through the streets of Brussels, some waving red Communist flags and chanting anti-fascist slogans, others waving green flags representing the Catholic movement and carrying portraits of the bishop of Recife, Dom Hélder Pessoa Câmara, the figurehead of the Brazilian progressive church for whom they demanded the award of the Nobel Peace Prize(55). The demonstration exemplified a coming together of experiences both from previous campaigns and from different traditions : the American civil rights movement's song We shall overcome was combined with traditional popular songs such Broeder Jakob (Frère Jacques), and activists throwing firecrackers were complemented by nuns staging a sit-in on the ground(56). Talpe and CEAL not only played a role in focusing the actions of the Catholic Workers' Youth in Communist and other radical groups, they were also crucial in cementing some ideological unity, by instilling the vision thatthe repression in Brazil was intrinsically rooted in economic factors and, more specifically, connected to the immoral effects of multinational corporations and global capital on Brazil's political and social climate. This concern with the role of economic factors was partly in line with the focus on this issue in FBI publications, which denounced Brazil's economic growth-praised by some observers as the 'Brazilian economic miracle' - and the strategy of multinational companies in Brazil as closely related to the rising tide of political repression(57).

Yet, the concern to explain the repression in Brazil in global and economic, rather than in Brazilian political, terms was equally stimulated by the idea that this positioning yielded tactical advantages. Through its focus on economic factors, this strategy aimed to bypass political dividing lines and to find common ground to unite Catholic and Communist groups. At the same time, and maybe more importantly, it could be used to justify the action of Belgian activists in support of a distant country by denouncing multinational corporations and economic globalization as global forces at work in Brazil as well as in Western Europe. With this message about Brazil, Talpe also found a receptive audience at the Catholic University of Leuven, where he started working as a researcher. Interest in the Third World and particularly in Latin America had been increasing at Leuven for some years(58). Stimulated by the presence of Latin American students, the Collegium pro America Latina, and connections to Belgian missionaries working in or recently returned from Latin America, students and a number of professors in Leuven had set up various projects to support Latin American countries(59). Against this background, the arrival of Talpe in Leuven provided a new impetus : the academic world offered him a new platform and he was able to publish his experiences and vision in a booklet entitled Brasil 70, published by the radical student group 'Third World Movement'(60). As in his speeches and other publications, Talpe emphasised the connections between the repression in Brazil and the situation of workers in Belgium and other Western countries. In these circles, CEAL and the Belgian section of the FBI which was set up by Talpe in Leuven, disseminated information through their publication, a translated version (in French and Dutch) of the Information Bulletin of the FBI, created in Algiers and Paris and featuring information on torture and political repression in Brazil. The bulletin was edited, published and distributed in Belgium by Bevrijdingsfilms in Leuven, an organization founded in 1968-1969 by the former missionary Paul ('Pablo') Franssens upon his forced return from Bolivia. This organization aimed to raise awareness of the struggle of the Third World through the distribution of alternative movies(61). It also distributed America Presse, a publication started in 1972 by Brazilian exiles in Paris to spread information about developments in Brazil and other Latin American countries and to help to break through the monopoly on news exercised by Western press agencies(62). Films about Brazil, such as the movie Os Fuzis (1964) by the film director Ruy Guerra, were screened and distributed amongst the Leuven student population via the FBI's network. Yet, the work of the former missionaries Talpe and Franssens and other members of CEAL to raise awareness of what was happening in Brazil should not be overestimated. The Belgian section of the FBI was in fact just a small group of people mainly concentrated in Leuven, together with some Brazilian students and a few dozen Belgian students. Paulo Roberto de Almeida, who while a student was one of the few Brazilians active in the Belgian section of the FBI, remembers how the activity of this informal group was dependent on the availability of information on the situation in Brazil, which proceeded mainly through correspondence or during occasional meetings with FBI sections in other European countries(63). Similarly, CEAL was run by a handful of volunteers who combined their support with commitments to a host of other organizations working in the area of peace and the Third World, and in comparison with which its activity, reach and impact were very limited. Indeed, CEAL was more a meeting place than a permanently operating organization, although it benefited from support in terms of organization and manpower of more professionalized organizations, notably Oxfam Belgium, or the BUVV. While the endeavors of Talpe and his group may well have been able to break the silence on the situation in Brazil in some quarters in Belgium, the lack of a concrete action plan impeded the whole endeavour. In the minds of the audiences they addressed, hearing and reading about the torture, repression and injustice in Brazil raised the fundamental question of what action could be taken to help the Brazilian people and opposition. If Talpe's compelling accounts- including a description of the torture of a pregnant woman and her unborn child - stirred the consciences of the Belgian public, which they did, then they also provoked feelings of impotence as much as feelings of solidarity. Talpe and CEAL may have gained some support from radicalized groups in Belgian society by joining the situation in Brazil to anti-authoritarian arguments and criticism of Western society, but the lack of a concrete action plan made the situation in Brazil more a theoretical textbook case-study and critique of society than an issue for concerted and sustained action. Even CEAL quickly began to turn its attention towards other Latin American countries, as a result of the opportunities offered by local study and action groups working around small but well-defined projects in other Latin American countries. For instance, the Latin America weekorganized by CEAL in 1971 featured teach-ins, film sessions, and meetings in which the issue of Brazil was overshadowed by a focus on aid projects in Chile, Uruguay, Bolivia, and Colombia, the latter due to the presence of a collaborator of the late revolutionary priest Camilo Torres (1929-66) in Belgium, who could talk about this hero of the radical liberation struggle in Colombia who was also a former student of Leuven(64). The problems in organizing action for Brazil were largely the same for other Europe Latin America Committees in Western Europe. The FBI collected and circulated information, both via contacts inside Brazil, who gathered information through personal networks and other sources, such as Brazilian opposition periodicals, and from newly arrived exiles and their testimonies. This information, then, was circulated from Paris, Algiers, and other sections of the FBI, which in 1970 had groups in eight Western European countries (Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, the UK, Sweden and Switzerland)(65). Newsletters, brochures, articles and letters were written by the FBI and its supporters, interviews were given to the press and media, but their effect seemed only very short-lived. Although interviews with Jan Talpe and other FBI members about torture, torture techniques, and the victims of torture, together with accompanying pictures, appeared in media outlets ranging from Swiss Radio and Television to a Caribbean journal and the prestigious German Der Spiegel, they failed to inspire concrete and sustained action from the wider public, and failed to make an impact amidst the constant flow of other news stories(66). The Russell Tribunal on Brazil New activities initiated by Brazilian exiles to change this situation did not at first have an effect on Belgian society. In the autumn of 1971, Brazilian exiles in the Chilean capital Santiago had, together with the Italian Socialist senator Lelio Basso, launched the idea of founding a Second Russell Tribunal on Brazil(67). Conceived as a follow-up to the famous Russell Tribunal on Vietnam composed of an international jury of intellectuals who publicly condemned American war crimes in Vietnam, the new tribunal was planned as the centerpiece of an international campaign denouncing repression in Brazil(68). Focusing on violations of democratic and human rights as a result of the malign impact of American involvement and multinational corporations in Latin America, the Tribunal wanted to tap into the increasing sensitivity to human rights' abuses and to involve a range of groups from various ideological backgrounds, notably Catholic organizations, since the Catholic church in Brazil faced increased repression(69). In the months following the launch of the initiative, Lelio Basso worked from Rome in cooperation with the FBI network to shape the plans for a tribunal, focusing especially on building a foundation base amongst Brazilian exile groups(70). The consensus that emerged after several months of contact and discussion resembled many of the tactical choices that had paved the way for the formation of the FBI more than two years earlier. Indeed, Basso and Arraes had succeeded by the spring of 1972 in rallying the support of more than twelve Brazilian political movements in exile, largely due to their ability to transcend political and ideological differences, focusing on attacking the Brazilian authorities by denouncing torture and repression in Brazil. This was all strategically based on the assumption that "everyone is sensitive to the question of human rights"(71). The Tribunal's denunciation of repression aimed not only to inform the wider public about torture and human rights violations, but wished also to unmask its 'systemic' roots and (what was seen as) its 'fascist' nature. Labels such as human rights and fascism were used without much theoretical foundation in what they actually involved, but because they seemed to be effective in forging some unity between Brazilian groups, and also served as a mean of attracting the interest of Western audiences. At first, however, Belgian activists were only occasionally involved in this initiative. At the request of the Tribunal's secretariat established by Lelio Basso in Rome and through the mediation of Leuven theology Professor Jan Grootaers, CEAL tried in vain in the summer of 1972 to recruit the Belgian Cardinal Leo Suenens as a member of the Tribunal's jury, which included, as well as Lelio Basso, figures likeJean-Paul Sartre and the Yugoslav historian Vladimir Dedijer(72). In the academic world, there was more success, astheTribunal gained the support of several academics, amongst them the Brussels scholar Pierre Mertens and the Louvain-la-Neuve professor François Rigaux, who would become vice-president of the tribunal in 1973. Indeed from 1973 the involvement of Western European groups in the organization of this tribunal grew, mainly because of the concern of Lelio Basso and the FBI to find financial support for the costs of the organization(73). At the same time, Belgian activists began to take a high profile in the organization of the tribunal : a number of academics and members of CEAL founded a support committee to gather financial and political support for the tribunal, advertising in several journals, ranging from CEAL's bulletin to academic journals like Pro Justitia. As the following section will make clear, the high profile of Belgian activists in this campaign was linked to the fact that Brussels was chosen by the Tribunal's secretariat in Rome and the FBI as host for the tribunal's inaugural session in November 1973. Belgium was the launch pad for an initiative that originated with Brazilian exiles in Chile and that was mainly realized in Rome and Algiers, because of its high strategic value : the Brazilian government planned to organize a grand international trade fair in Brussels in November 1973, Brasil Export. II. The Campaign against "Brasil Export" 73 In January 1973, an intelligence source in the Brazilian embassy in Brusselstold the FBI about the Brazilian government's plans to organize a trade fair promoting national products and industry to the European market in Brussels in the autumn of that year(74).

The fair was to be a sequel to the prestigious trade fair Brasil Export 72 in São Paulo, and formed part of the Brazilian government's attempts to expand its export-focused trade policy through increased access to the European market and through attracting foreign investment. Indeed, since the late 1960s, the Brazilian government had succeeded in creating impressive economic growth, growth that nonetheless increased both political repression and the already high disparities in income distribution(75). Western Europe was one of Brazil's most important markets, facilitated by a series of bilateral economic treaties with Western European countries(76). The plans for a trade fair in the heart of Western Europe were, however, not only inspired by economic motives, but were just as much part of a Brazilian diplomatic charm offensive to counter the increasingly negative publicity about repression and terror in Brazil(77). About 350 exhibitors were due to attend the trade fair, organized in the Heizel Congress Palace in Brussels in November 1973, and the whole event also included plans for a broad range of cultural events(78). In response, the FBI leadership decided to seize on these plans as a unique opportunity to draw international attention to the situation in Brazil and to breathe new life into the slumbering campaign for the Russell Tribunal on Brazil. Yet, after consultation between the FBI sections and Europe Latin America Committees in Western Europe, it was decided to focus on organizing protests in Belgium, as activists in other countries did not see many opportunities for effective campaigns outside Belgium(79). In the spring of 1973, CEAL's members started to enlist a variety of organizations and groups around the issue of Brasil Export and the planned protest campaign(80). Pierre Galand and Isabelle Blume worked mainly with the Belgian Socialist and Communist movement, contacting parliamentarians, youth and peace organizations, and trade unionists(81). Jan Talpe and Conrad Detrez reached out to groups at universities, Catholic organizations and progressive church communities. In their quest to involve Catholic groups, CEAL publicised the message of the progressive Brazilian bishops who in May 1973 had publicly spoken out against social injustice and human rights violations in Brazil(82). The text was published by the Catholic NGO Broederlijk Delen/ Entraide et Fraternité in cooperation with CEAL(83). Alongside this activity, Talpe wrote articles about the situation inside Brazil and CEAL's own newsletter circulated information about opportunities for organizing protest.

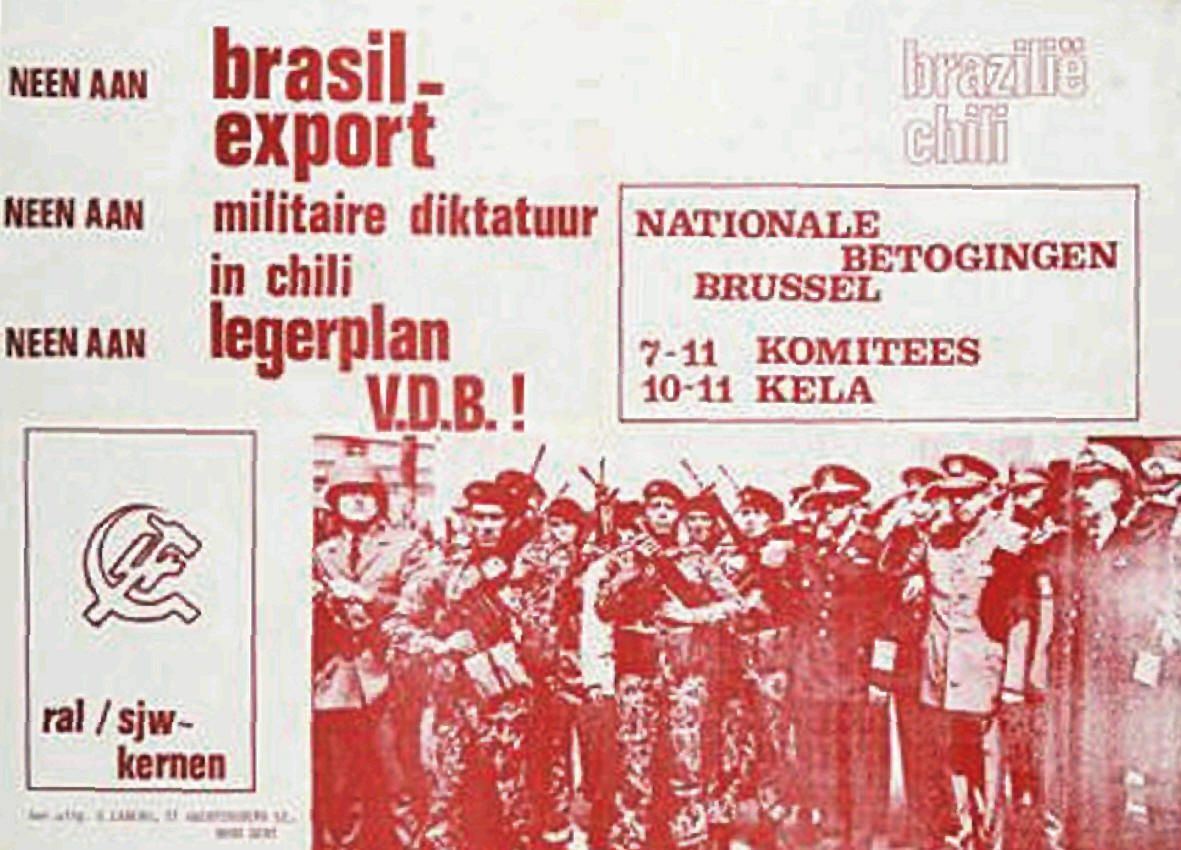

International causes turned into domestic issues. Poster for demonstrations which welded protest against the trade fair Brasil Export to denunciations of the 1973 coup in Chile and protest against the army reform plans of the Belgian government in November 1973. (Archives AMSAB-ISG) In developing these contacts, the leading members of CEAL quickly realized importance of embracing a broad framework which could both match the campaign against Brasil Export with the interests of a wide variety of Belgian organizations with differing perspectives, and which could also rally them behind the same common goals. The importance of couching the protest against Brasil Export in a flexible framework became very clear during a meeting organized in June 1973 by CEAL in the Maison des Huit Heures in Brussels which brought together more than fifty individuals representing about thirty organizations interested in taking action against Brasil Export, ranging from the BUVV to representatives of the international trade union confederation World Confederation of Labour (WCL)(84). At the meeting, discussions about the campaign, and more specifically, about the position of the FBI emerged. Whereas the functioning of CEAL and its vision of the campaign against Brasil Export was closely related to the goals of the FBI, for several participants, such as representatives of the Communist peace organization BUVV and the trade unions, it was important to keep protest against the international fair separate from support for the FBI. Largely unknown to most of the participants, and associated too closely with the complexities of the Brazilian resistance and dividing lines between exiles which were difficult for non-exiles to understand, the role of the FBI was not recognized by all participants. Members of the Belgian Communist party were especially skeptical, as they were in contact with exiled members of the Brazilian Communist Party, which contested the legitimacy of this self-declared unitary organization led by the Socialist Arraes. As a tactical response to these objections, the leadership of CEAL underplayed the role of the FBI in the campaign against Brasil Export by deploying an argument which focused on the pernicious role of global capital and multinational corporations in the repression and exploitation of the population in Brazil, and by extension in other parts of the world, including Western Europe. With this move, CEAL thus protected itself from the accusation that it was using the campaign against Brasil Export to pursue the FBI's political or ideological agenda. In focusing on economic globalization rather than political solidarity, CEAL made a key tactical choice that served strategically to frame the campaign against Brasil Export for its supporters, and eventually for the broader public. This choice was inspired by the widespread prevalence of 'dependency thinking' in various groups in the early 1970s. Dependency theory referred to a clutch of doctrines popularized by the writings of intellectuals such as Andre Gunder Frank and (future Brazilian president) Fernando Henrique Cardoso, stressing the existence and dynamics of an international capitalist system which was driven by unequal and inequitable economic flows between the developed centre and underdeveloped periphery countries and which held the poor South in the grip of the North(85). What rendered this thinking so attractive was not so much its theoretical sophistication, developed in academic debates, but rather its simplicity in drawing parallels and connections between the situation in the Third World and Western Europe and vice versa.Dependency theory brought together a range of interests and opened up the possibility of working locally in a supposedly global battle against the global forces of capital. It also spread the belief that actions in distant societies mattered both for the Third World and for the activists who took action in their own societies. The choice of this framework allowed the different groups participating in the campaign against Brasil Export to adopt different positions. It was a framing device in which many groups could find something to fit their own beliefs, and join protest against Brasil Export to their own agenda. Groups close to trade union and workers' organizations, for example, stressed the pernicious impact of multinational corporations on labor conditions, and linked the fair to the allocation of industrial sites to the Third World. They turned Brasil Export into a symbol of the global impact of multinational corporations, a topical issue given the restructurings and redundancies taking place in many multinational corporations active in Belgium as the consequence of the growing competition from developing countries, as in the most famous case of AKZO in 1972(86). Amongst more radical student groups, Brasil Export offered opportunities for political argument, with the primary emphasis on criticism of the Belgian political elite that had given permission for the fair. NGOs active in Third World development, such as the National Centre for Development Cooperation (NCOS/CNCD), used Brasil Export to denounce the export-oriented policy of the Brazilian government (praised by its sympathizers as the 'Brazilian miracle') as an inhumane development model that increased social injustice and inequality(87). Human rights organizations such as Amnesty International justified and focused their accounts and action against Brasil Export on accusations of human rights violations by the Brazilian government. Some Christian groups combined concerns about social injustice in Brazil with the message of the Brazilian bishop Hélder Câmara, who visited the country in the summer of 1973, and referred to the declaration of the Brazilian bishops conference which contained a condemnation of the military dictatorship. This diversity of approach became clear in the variety of posters produced for the campaign against Brasil Export, which used different images to attract attention: one model placed the names of a number of multinational corporations that were fought against by rural indigenous workers and armed resistance at the centre; another featured pictures of people tortured by the Brazilian police; and others used the traditional images of children to draw attention to social injustice in Brazil(88). The upcoming launch of the national campaign 'No to Brasil Export' from September 1973 until the end of the trade fair in November, spurred organizing efforts during the preceding summer. There was a large escalation of activity across the country : local and regional coordinating groups or committees were established by an alliance of people and groups from various organizations and backgrounds, distributing posters, booklets and leaflets, and staging meetings where Talpe took the floor. Jan Talpe, Pablo Franssens, Pierre Galand and a handful of other core CEAL activists strengthened the connections between these groups, and stimulated their activity by providing fresh information and dimensions of unity. As part of these coordinating efforts and, more specifically, to steer the campaign in Flanders, KELA (Komitee Europa Latijns Amerika) was established as the Flemish counterpart of the mainly French-speaking CEAL through the collaboration of Flemish activists from organizations such as Elcker-Ik, Sago, the Catholic Workers' Youth, Pax Christi and Oxfam-Wereldwinkels. It was responsible for disseminating information in Dutch and the coordination of activists in Flanders(89). Local and regional groups contacted politicians in their respective districts, and wrote letters to members of the Belgian government. Pierre Galand raised the issue of Brasil Export at a personal meeting with the Socialist Prime minister Edmond Leburton. Through members of groups involved in the works of CEAL, such as the Catholic Workers'Youth and the Young Socialists, the issue was also raised in the Christian-Democratic and Socialist political parties which were both in office. Though CEAL's campaign had the support of some individual politicians, these parties eventually refused to take a position against Brasil Export at governmental level(90). The position of the Socialist and Christian trade unions was also rather ambivalent. On the one hand, both trade union organizations started to raise their membership's awareness from the summer of 1973 onwards, drawing on information provided by CEAL. They brought the issue to their respective international confederations, the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) and the World Confederation of Labour (WCL), and condemned the fair in the autumn 1973 with joint public statements(91). On the other hand, however, they were reluctant to engage in common action with the random assortment of more radical groups which were planning a large-scale national demonstration in November and which were often critical of the 'Old Left'. Although, as mentioned above, the FBI had decided to focus action on Belgium relatively quickly, this did not mean that Belgian activists worked exclusively on Belgium-only events. Information about the action against Brasil Export in Belgium was communicated to other FBI sections in Western Europe, Latin America and the US in an effort to combine action in Belgium with supporting action in other countries(92). CEAL and other members of the FBI network also lobbied international organizations such as Pax Christi, the ICFTU and WCL to engage in action against Brasil Export and to denounce it publicly at international level.

Cover of a 1973 booklet published by the Committee of Solidarity with the Brazilian People in Geneva and denouncing the "Brazilian economic miracle". This Swiss committee called for participation in protests against the Brasil Export 73 fair in Belgium, and also launched a campaign for the release of the imprisoned and tortured resistance leader Manuel da Conceição. (Source : Comité de solidarité avec le peuple brésilien, Brésil 73. "Le miracle économique par le sang du peuple", Geneva, 1973) Building on the good relations of some members of CEAL with the WCL, the latter helped raise the profile of the campaign against Brasil Export among its affiliated Latin American trade unions. Some Latin American trade unions could be mobilized into action via the WCL's regional Latin American confederation CLAT, whose leader Emilio Máspero had good relations with CEAL member Isabelle Blume(93). In Colombia, the trade union CGT (Confederación General del Trabajo) staged for instance some small-scale public demonstrations against Brasil Export in front of the Brazilian embassy in Bogota, encouraged by the idea that in Brussels, at the other end of the world, Belgian activists were mobilizing at the same time for the same cause(94). When the national 'No to Brasil Export' campaign started on 7 September, symbolically chosen to coincide with Brazilian Independence Day, more than one hundred organizations had been mobilized. Provocatively, activists organized a march to the Brazilian embassy in Brussels for the symbolic return of a box of stolen exhibition material(95). In the following weeks, the network of groups and organizations coalescing around CEAL and KELA created an impressive level of activity. Local groups organized film sessions, distributed leaflets, and staged discussions with Jan Talpe and his fellow revolutionary former missionary Pablo Franssens. Laden with Brazilian movies, books, and other information provided by the FBI as well as with personal stories, Talpe undertook a packed schedule of speaking tours, taking the floor in virtually every major town in Belgium(96). His audiences ranged from Catholic organizations to radicalized student groups, who took to the streets and confronted the police during demonstrations. In Leuven, his lecture on Brazil was followed by a demonstration against Brasil Export by 400 students. In Brussels, a Molotov cocktail was thrown into the buildings of Solvay by a student group which claimed to support the murdered Brazilian resistance leader Carlos Marighella, whose memory was cultivated and spread amongst students by his biographer and CEAL member Conrad Detrez. In Antwerp, about twenty activists defenestrated documents and Brasil Export publicity material at the Brazilian consulate, before being arrested by the police(97). An example of a more peaceful local activity is provided by the provincial city of Mons, where a committee against Brasil Export was formed by Christian, Communist and Trotskyite activists(98). Here, some Christian activists took the initiative, impressed by the figure of the Brazilian bishop Dom Hélder Pessoa Câmara during his visit to Belgium in the summer of 1973(99). In the province of East Flanders, the Belgian Communist Party participated with youth groups in the organization of action across several towns(100). When, only four days after the start of the campaign, the situation in Chile suddenly made the headlines after Pinochet's coup and the overthrow of President Allende on 11 September, Latin America seemed to be dominating the news. The campaign against Brasil Export which had been developing since mid-1973 provided the basis for the quick mobilization in Belgium against the coup in Chile, both organizationally and ideologically. CEAL and KELA included the issue of Chile in their campaigns against Brasil Export. Under the slogan 'Brazil and Chile, the same dictatorship, the same solidarity', multinational corporations and their imperialism in the Third World were held responsible for the repression in both countries(101). The wide-scale promotional activity of the Brazilian government further incited activists. In Brussels alone, according to the leading Brazilian newspaper O Globo, there were more than 360 posters of a Brazilian cup of coffee promoting the exhibition(102). Likewise, all the Belgian mainstream newspapers repeatedly published large advertisements paid for by the Brazilian government to promote Brasil Export. Unintentionally, they were the best publicity the activists could have. Coinciding with week of action for Brazil, the inaugural session of the Second Russell Tribunal on the repression in Brazil and Latin America took place in Brussels on 6 November 1973, the day before the official opening of Brasil Export(103). Brasil Export had indeed acted as a spur to the progress of the Second Russell Tribunal(104). In line with the request of the tribunal's secretariat in Rome, CEAL had mobilized interested organizations to form a support committee for practical assistance with the organization of the tribunal, and to promote this initiative in Belgium. The organizational heart of this support committee was the secretariat of the Belgian League for the Defence of Human Rights in Brussels, whose president Georges Aronstein and the lawyer François Rigaux were, together with CEAL, the driving forces(105). The initial meeting in Brussels was attended by a number of intellectuals including the American sociology professor James Petras (former advisor of Salvador Allende), the French mathematician Laurent Schwartz, and Lelio Basso, as well as representatives of support committees from other European countries. The attendees, however, formed only a small part of a much bigger group which supported the Tribunal, including more famous figures like Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Nobel prize-winners George Wald and Alfred Kastler who had been contacted by the secretariat in Rome(106).